BY LACEY ROSE | HollywoodReporter.Com

Troy Warren for CNT #Entertainment

The ‘Shrink Next Door’ producer-star on building (and winnowing) his empire, splitting with collaborator and pal Adam McKay and chasing the funny above all else: “I’ve always loved making other people laugh. I’ve just never needed to make you like me.”

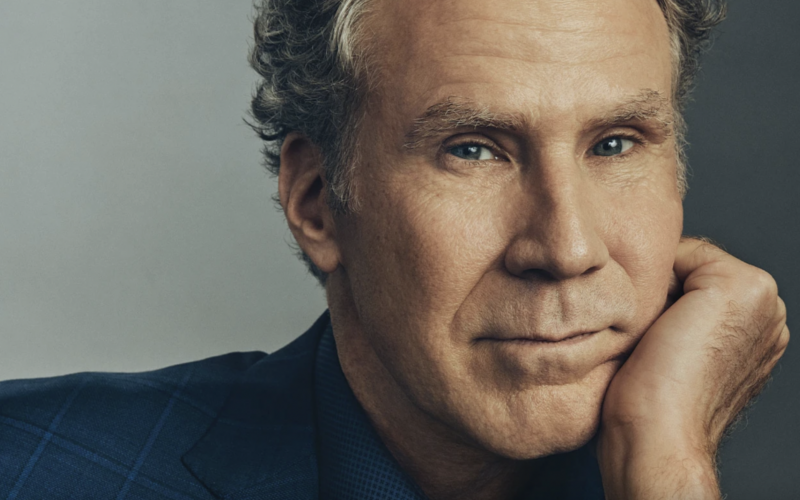

I’ve yet to turn on my recorder and Will Ferrell is already apologizing. He’s rusty, he says, as he pours us both coffee.

It’s been a while since he sat for a lengthy interview, the kind that requires him to reflect on his career and his place in a fast-changing business. And he’s not so sure he’s any good at it (he’s wrong), or that he’ll be able to gin up the kind of anecdotes I’ll need (he does). At one point, he tells me he’s not a particularly good movie star; in fact, there are days he’s convinced he may be a pretty bad one. He and Ryan Reynolds, with whom he’s here in Boston to film a big, splashy Christmas musical, talk about this a lot.

“We feel like we’re constantly letting people down,” says Ferrell, all 6-foot-3 of him folded into an armchair in his sparsely decorated Beacon Hill rental, where he’s been holed up, away from his wife and three boys since May. “People come up to me all the time, like, ‘Oh my gosh, it’s you! Do something funny!’ and I don’t know what I’m supposed to say.” He admits he’s skilled in the art of pulling down his baseball cap just enough to obscure his identity as he walks by crowded college bars — though he’s gotten better at playing the part of Will Ferrell in public, too. Just the other day, he’d been golfing with some buddies when a few young guys, squarely in the Ferrell demo, called out to him, “Can we get a photo?” To their delight, and his, he was ready with a response. “It’s a hundred bucks,” he shouted back, and they all howled.

Making people laugh — his fans, his collaborators, himself — is still a priority for Ferrell. Sure, the 54-year-old has dabbled in more dramatic fare, including his upcoming turn, opposite Paul Rudd, in the anticipated Apple TV+ series The Shrink Next Door (dropping Nov. 12); but he’s not looking to turn his back on the genre that made him famous, nor is he desperate to be taken seriously in the way so many of his predecessors were. You won’t see him pursuing straight-up Oscar bait, or using his work to make pointed political statements, even if the winds of comedy have blown in that direction. And while he’s not going to throw shade on projects that set out to say something — “because those are great,” he says, “and more than needed” — he wants to laugh at unabashed silliness again, and he’s hopeful you do, too.

“There’s just so much going on in the world, and sometimes it’s nice to turn your brain off,” says Ferrell, who’s reminded of one of his heroes, Steve Martin, who has talked about comedy in the 1970s this way. “Coming out of the ’60s, which were so contentious, Steve was like, ‘Everyone’s doing message comedy, and I just want to walk out with an arrow shooting through my head,’ and that’s kind of how I feel right now.”

As a prolific producer of both film and TV, responsible for such hits as Hustlers, Barb and Star Go to Vista Del Mar and HBO Emmy winner Succession, Ferrell has considerably more clout than he lets on. But push him on that budding empire — which, until its recent sale, included comedy hub Funny or Die — and he says things like, “It kind of fell into my lap.” In truth, he’s not even sure he’s comfortable with the idea of an empire, which was at the root of his split from his longtime collaborator and partner in Gary Sanchez Productions, Adam McKay, in 2019. “Adam was like, ‘I want to do this, and this, and this’; he wanted growth and a sphere of influence, and I was just like, ‘I don’t know, that sounds like a lot that I have to keep track of,’ ” says Ferrell, discussing the breakup publicly for the first time. “To me, the potential of seeing a billboard, and being like: ‘Oh, we’re producing that?’ I don’t know. … At the end of the day, we just have different amounts of bandwidth.”

Ferrell acknowledges that there’s big business in that other model — Reese Witherspoon’s production company recently sold at a valuation of $900 million, after all — it’s just not what he’s after. “He wants to be able to talk to the filmmakers, and read the scripts — he wants to be able to show up,” says his producing partner, Jessica Elbaum. Still, he shrugs off questions about strategy, and winces at the concept of a five-year plan. As he said in his first round of general meetings after leaving Saturday Night Live, “What am I interested in doing? I don’t know. More funny stuff?”

The Shrink Next Door was the first limited series to come Ferrell’s way, or at least the first one brought to his attention, and there wasn’t a whole lot of deliberation.

He devoured the popular podcast on which it’s based, which detailed the intensely bizarre, codependent relationship between real-life psychiatrist Dr. Isaac “Ike” Herschkopf and his longtime patient Martin “Marty” Markowitz that devolves into the former taking over the latter’s life, complete with his home and family business. Ferrell and Rudd were already down the road before settling on who would play who, though both say there wasn’t much debate there: Rudd would be Ike; Ferrell would play Marty. It was only later, once they decided they’d try to capture the essence and heavy New York accents of the real people, that Ferrell began to see the heavy lift it would be.

The role required that Ferrell work closely with a dialect coach and pore over a collection of old home videos. He spent time with the real Marty, too, along with his sister (who’s played by Kathryn Hahn) at Marty’s house in the Hamptons. The times that Ferrell had played real people in the past were primarily for sketches, and here he’d need to sustain a character through eight episodes and a roller coaster of emotions. Then the pandemic hit and, for a time, he feared all that prep would be for naught.

Production eventually moved from New York, where the story takes place, to L.A., which complicated the project but delighted Ferrell, who would be able to come home to his wife and sons, now 17, 14 and 11. But all the stops and starts only contributed to the general anxiety surrounding the dark comedy, which was weighty enough without a deadly pandemic hanging over it. “It definitely pushed me beyond my comfort zone,” says Ferrell, “but I’m getting more interested in doing things that scare me to death.”

Rudd, who’d worked with Ferrell on the Anchorman films, says he was struck at how committed his co-star was: “Normally, when you’re done shooting, everyone just goes right to their phones, but I don’t think I’ve ever seen Will with a cellphone,” says Rudd. “He never brought one to set, ever, and so I did the same, which meant when we weren’t shooting, we would hang out and we’d read lines and we’d talk. And that’s the thing about Will — he’s always kind of present.” (Elbaum, who’s worked with Ferrell for 18 years, first as his assistant and now as the head of his production company, says it’s the same on every set as it is at mealtime and at home with Ferrell: “He was one of the last people to even get a cellphone,” she says. “He’s just not that guy, and it sets the tone, because then people engage.”)

Shrink Next Door finally wrapped this spring, leaving Ferrell with only a few weeks before having to relocate to Boston for seven weeks of rehearsal on Spirited, his modern musical rendition of Charles Dickens’ A Christmas Carol, also for Apple, with Reynolds and Octavia Spencer. It’s been a different kind of hard, he says, of the singing and the dancing and the recording of tracks written by Justin Paul and Benj Pasek of La La Land and Dear Evan Hansen fame. But there’s an emotional component to the comedy as well, which he hadn’t entirely anticipated. “The whole point of the movie is that the ghosts of Dickens’ Christmas Carol, who pluck a Scrooge every year to show them the error of their ways and then they’re like, ‘I will be a better person’ — there’s a crisis of faith in that, like, what [the ghosts] do, does it even work anymore? That’s what we’re examining,” says Ferrell, who plays the Ghost of Christmas Present. “So yes, it’s really fun and there are great songs, but I also had moments of, ‘Wait, I’m crying in this now, too?’”

During a break from production, Reynolds tries to sum up what makes Ferrell uniquely suited for the role: “If I had to distill it down to a soundbite, which is unfair to Will, I’d say that I see a person who very easily accesses vulnerability,” he tells me. “And vulnerability is both heartbreaking and funny — and Will Ferrell lives at the intersection of heartbreaking and funny. He eats dinner off of the intersection of heartbreaking and funny.”

***

Way back at the beginning of Ferrell’s career, when he was still working his way up at The Groundlings, he had lunch with his father, an on-again, off-again keyboardist for The Righteous Brothers, to discuss his future. Lee Ferrell told his son that if success in the entertainment industry were based solely on talent, he wouldn’t worry at all about Ferrell; but there was an awful lot of luck involved, too.

“So, if it doesn’t work out, it’s not you, and don’t ever be afraid to just hang it all up and do something else,” Ferrell recalls hearing. He adds now of his dad, who’s still occasionally playing music at 79: “That was one of his quiet regrets, that he’d just gone down the road because he didn’t know what else he could do.”

It wasn’t your average pep talk, but Ferrell says it took all the pressure off. If he wasn’t going to make it, he might as well enjoy the ride. For years, he and his father, who had split with his educator mom when Ferrell was 8, would have regular check-ins. “We were always talking about what else I could do,” says Ferrell, who’d later recruit his wife, Viveca, to the exercise, even after he was headlining blockbusters. “Literally, Viv and I would drive around, like, ‘Gosh, if it all goes away, maybe we can have a dog grooming thing?’ I think I finally stopped thinking about alternatives about 10 years ago.”

From the outside, whatever contingency planning was going on should have come to an end in 1995, when Lorne Michaels hired him on Saturday Night Live — even if one prominent critic had called Ferrell “the most annoying newcomer,” which he wore like a badge of honor. In fact, Ferrell had the descriptor mounted on a nameplate and hung on his office door. “You have a choice with that stuff: to read it and believe it,” he says, “or to just laugh at it but also kind of dig in and go, ‘Oh, you hate me? You haven’t even begun to hate me.’ And that’s my competitive side, that, ‘Oh, just wait, I’m going to go at it even harder.’” (For the record, Michaels never wavered on his pick: “I never rank, but Will’s definitely in the top two or three that have ever done the show,” he says. “There’s no question.”)

Early on, Ferrell established himself as an ensemble player, as willing to lead sketches as he was to play in the background — though the memory Michaels shares isn’t about that or his beloved impersonations. (Ferrell’s George W. Bush has been credited with helping to get the former president elected.) Instead, it was right after Sept. 11, and the Saturday Night Live boss had been determined to go on the air, as he was in 2020 during the pandemic. “I’d made it clear that I was going to show up but that the cast should only do so if it wanted to — because I didn’t know what the risks were, and everybody, the whole city, was frightened,” says Michaels. “And so, it must’ve been 10 or 11 on that Friday night, and we were blocking some sketch, and I just made eye contact with Will. Neither of us knew how it was all going to turn out, but I remember the moment because, for both of us, there was just a level of, ‘This is what we do.’”

Ferrell is often asked about his favorite SNL memories, and he can never seem to muster a good answer. But he’s been thinking about it lately, and he’s certain one of them would have to be from early in his tenure, standing just offstage, listening to the studio audience erupt in laughter during Molly Shannon’s first outing as Mary Katherine Gallagher. Back then, he and Shannon were part of a largely new cast in a tenuous transition period for the show. “And that was the first time I heard the audience really shriek, and I still get goosebumps thinking about it,” says Ferrell. “I just remember it being, like, ’Oh, wow, I think we might be OK here.’”

That one of Ferrell’s favorite memories revolves around someone else onstage getting all the laughs is telling — it is also in keeping with everything everyone has told me about him. In fact, Kristen Wiig prefaces her praise with, “I’m sure I’m not the first person to tell you this,” and then says: “Everybody loves Will, and it’s not just because he’s funny. I really think you can see people’s personalities — you can even read a bit of people’s energies when you see them onscreen, and he just pulls you in. He’s a good guy and he’s really good at what he does.”

***

After seven years at Saturday Night Live, it was time for Ferrell to hang it up. He and his auctioneer wife moved back to Los Angeles, where he’d make the rounds and reintroduce himself to Hollywood. By then, he’d already shot Old School, though the R-rated comedy was being held by a jittery studio. What he’d learn later is that the director, Todd Phillips, had had to fight for Ferrell to star as “Frank the Tank,” a new dad hurtling toward self-destruction. “There were people who didn’t like the idea of me in that role, but I never found out who,” Ferrell says, and it didn’t much matter: Old School was released in early 2003 and became a surprise hit, capturing the zeitgeist and $87 million at the box office.

Elf followed later that year, and though the feel-good Christmas comedy would prove another home run, Ferrell still remembers running around New York in his silly yellow tights, thinking, “Boy, this could be the end.” Before its release, they’d held a series of test screenings. Ferrell’s manager would call with updates: “He was like, ‘Well, the family one went great, but we could really get eviscerated in this next one. I’m looking at a bunch of what look like USC frat boys about to go in,’” recounts Ferrell, once a USC frat boy himself. “Then later I hear, no, that group actually liked it, too.” The low-budget PG comedy generated raves — except from The Washington Post, which declared it “the first and possibly the last Will Ferrell star vehicle” — and $220 million at the box office, cementing Ferrell’s status as a bona fide movie star. (A sequel was written, which would’ve paid him $29 million had Ferrell not balked at its rehashed premise. He says the decision to walk away was simple: “I would have had to promote the movie from an honest place, which would’ve been, like, ‘Oh no, it’s not good. I just couldn’t turn down that much money.’ And I thought, ‘Can I actually say those words? I don’t think I can, so I guess I can’t do the movie.’”)

In remarkably quick succession, he released two more cult classics: 2004’s Anchorman: The Legend of Ron Burgundy (which grossed $91 million) and 2006’s Talladega Nights: The Ballad of Ricky Bobby ($163 million). The Atlantic praised both, calling them “surreal satires of American arrogance [that worked] because the title characters are earnest creations — buffoons invested with the genuine belief that what they’re doing is special.” But Ferrell wasn’t just the buffoon at the center; he’d co-written the films, too, with his SNL pal McKay. Soon, the red-hot pair would form a production company, comically titled Gary Sanchez Productions, after a fictional Paraguayan financier, and co-write Step Brothers and an Anchorman follow-up, which “was a sequel worth having,” in Ferrell’s estimation.

It was during that period that Rudd got to know Ferrell. “I remember being on the set of Anchorman, and he’d just say these things in the moment, like [the now-famous line] ‘Milk was a bad choice,’ and I thought, ‘God, this is a really funny person being funny in ways I haven’t seen people be funny before,’” he says. “And what really struck me was that Will was doing it seemingly without a neurotic bone in his body. It didn’t make sense that someone that funny really didn’t seem insecure in the ways that so many funny people are.”

Michaels has long been convinced that Ferrell’s towering height and the stability of his personal life contribute to how almost preternaturally well-adjusted he is. “There’s a phrase, ‘Some people just spill over.’ With being funny, there’s a neediness, there’s an anger, there’s a lot of other things that go with it,” Michaels says, “but what Will does is focused, and there’s always something charming and fun about it.” Ferrell has spent years trying to explain what it is that drives his comedy, and this is the closest he’s come: “I’ve always loved making other people laugh, but I’ve never needed it,” he says. “I’ve never had the need to have to make you like me.”

In the span of a few years, Ferrell had become one of the most consistent box office draws in the business, regularly commanding $20 million paychecks and, later, the Mark Twain Prize for American Humor. “I mean, you’d struggle to find any modern actor who’s as quotable as Will Ferrell, and half the time people are quoting him, I’m not sure they even realize they’re quoting him,” says Reynolds, who calls Ferrell his comedy idol. But there were misfires, too, and Ferrell remembers those just as clearly. Before Talladega Nights, there was the 2005 fantasy rom-com Bewitched, which didn’t work on a number of levels. “And something like that, it brings you down a peg,” says Ferrell. More followed, most recently Holmes & Watsonin 2018, though none hit quite as hard as the 2009 bomb Land of the Lost, which was released the same weekend as Phillips’ The Hangover.

Ferrell was in New York doing press at the time. “I’ll never forget, [the movie] had had a terrible Friday night, and I wake up Saturday morning and I’m about to go for a jog, and you literally start wondering, are people going to point, ‘There he is! His movie underperformed!’ And then you finally go and nobody gives a shit,” says Ferrell. “And that same night, I go out to dinner, and this guy sees me in the bathroom, and he’s like, ‘Land of the Lost!’ I’m thinking, ‘Oh no, here it comes,’ and he goes, ‘That was so funny. Oh my God, when you poured the dinosaur pee all over! Congrats, man.’ And it was a good reminder that there’s the movie business and then there’s the world. So yeah, your skin gets thicker, and you learn to shake it off. And it does get easier over time.”

***

Mixed in with the big, broad, commercial comedies, which will always be the bread-and-butter of his business, is the wackier fare that can feel like it’s just for Ferrell: the ridiculous beer commercials he released only in obscure markets, or the silly color commentary he and Molly Shannon provided for Prince Harry and Meghan Markle’s wedding on HBO. The fact that his admittedly “weird” ideas often leave people scratching their heads only makes them funnier to Ferrell. Plus, he says, “I love just kind of keeping everyone on their toes.”

Starring with Wiig in a dead-serious 2015 Lifetime thriller about an ill-fated adoption, aptly titled A Deadly Adoption, was easily the wackiest of them all. “I woke up one day with Lifetime on, and I thought, ‘Wait a minute, wouldn’t it be funny if you saw me and maybe another known comedy person do a Lifetime movie and just play it straight? Yeah, got to do that,’” says Ferrell. Convincing his team of representatives — most of whom have been with Ferrell since the beginning — that the $700,000 project was a good use of anyone’s time proved a challenge; Wiig, however, was immediately in. “Are you joking? I didn’t even need to know anything more,” she says, adding of Ferrell: “To watch someone go through their career with that kind of ‘Why not?’ attitude — to truly come from a place of, ‘This would be so funny to do’ — I mean, that’s what you want, right? That’s inspiring.”

One doesn’t need to spend much time with Ferrell before other ideas, at various stages of gestation and feasibility, begin spilling out. On this day, he’s fixated on an a cappella musical idea that centers on the Russian Red Army’s men’s choral group, which, you may remember (but probably don’t), caused momentary internet hysteria at the 2014 Olympics’ Opening Ceremony, when its members performed the Daft Punk song “Get Lucky” without a whiff of irony. (Just google it.) “So what I want to do,” he says, practically giddy, “is a Broadway show of the Russian Red Army: We’d sing pop songs, and make comments about the differences between the U.S. and Russia, and how the Russians are so much better. It would be satirical, and really funny — I’m still working it all out, like, how to get it up on its feet.”

Elbaum keeps a list of every one of Ferrell’s screwball ideas, and then waits to see if he brings them up a second or third time. “It’ll be months or sometimes years, and he’ll be like, ‘You know, I could maybe write that thing,’ and once Will wants to do something, you do it,” she says, both because he’s able to galvanize everyone around his ideas and because he’s determined to see them through. “Also, I’m sorry, if you’re sitting with him and he pitches you this idea of, like, ‘I want to do a movie entirely in Spanish’ [as Ferrell did with 2012’s Casa de Mi Padre], you’re like, ‘Yes, of course, of course we’re going to do that.’”

It was Elbaum who had come up with the idea for Gloria Sanchez Productions, which now houses all of their projects. It was initially conceived as a sister label to the now-shuttered Gary Sanchez Productions — and when she pitched it to Ferrell seven or eight years ago, nobody was launching female-driven companies, much less greenlighting projects from them. What neither of them could have predicted was just how relevant the company and its mission would become in the #MeToo era. Suddenly, Ferrell was uniquely positioned on two ends of a cultural shift. As a producer, he has had a slew of timely projects, with more coming from Barb and Star’s Wiig and Annie Mumolo along with Lena Dunham and Constance Wu, which he’s nurtured with Elbaum and their tiny staff. But as a male comedy icon, arguably the biggest of his generation, who had built his brand on outlandish frat-boy comedy, the past few years proved more challenging — or they would have, if Ferrell were focused on what the marketplace was demanding. But he’s never been particularly interested in chasing the zeitgeist. “If it’s a funny idea to me,” he says, “I’ll put it out there and see.”

So, as Ferrell’s peers pulled away from laugh-out-loud funny and focused instead on female ensembles and message comedy, he wrote and starred in Eurovision Song Contest: The Story of Fire Saga, a slightly too long, totally absurd Netflix film about a lovable Icelandic rube with visions of triumphing at the titular song competition. What happened next seemed to surprise everyone but Ferrell: Audiences wanted to laugh again. Vanity Fair said it was “a relief to see entertainment that’s silly and fabulous,” and New York magazine called it “the most emotionally engaging movie Will Ferrell has ever made.” Ferrell’s phone has not stopped ringing since — if only he had it on him.

In Other NEWS