BY GARY BAUM, EVAN NICOLE BROWN

Troy Warren for CNT #Entertainment #Lifestyle

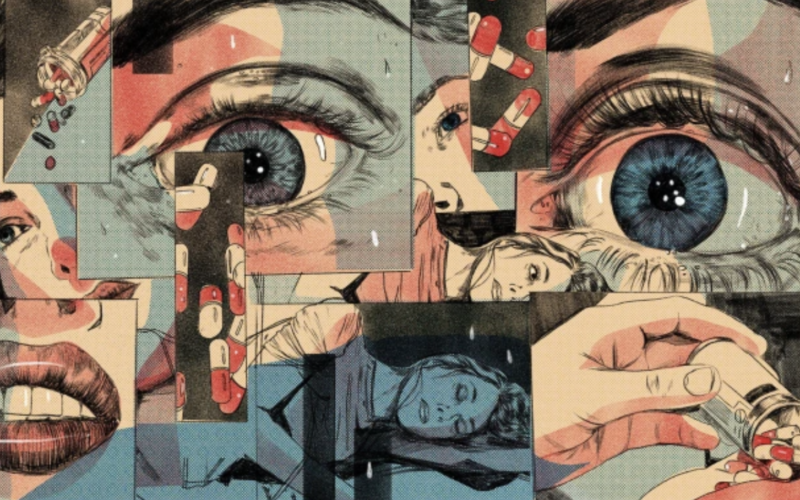

The ultra-powerful synthetic painkiller is increasingly mixed with other drugs, from cocaine to Xanax and Adderall, leading to a spate of high-profile overdoses and deaths across the entertainment community: “People often don’t know that they’re taking it.”

On Saturday night, Sept. 25, the LAPD dispatched officers to the $16 million Brentwood home of Richard Lovett, a parent and the president of CAA, to respond to a large party of high schoolers from the city’s private school scene. The police didn’t only disperse the gathering at the house — which is near the mansion used as the exterior for The Fresh Prince of Bel-Air — but responded to two drug overdoses, one of which The Hollywood Reporter has learned was the consequence of unintended ingestion of the ultra-powerful synthetic painkiller fentanyl. Both minors survived.

Lovett declined to comment about the previously unreported incident, which followed a deadly Venice house party two weeks earlier, when three comedians and television writers — Fuquan Johnson, Natalie Williamson and Ricky Angeli — succumbed after taking fentanyl-laced cocaine. A fourth friend, comedian Kate Quigley, was hospitalized and released.

The day before the overdoses at Lovett’s home, the New York Chief Medical Examiner confirmed that actor Michael K. Williams — best known as Omar Little on The Wire — had died after overdosing on a combination of heroin, cocaine and fentanyl earlier that month. And recently it was revealed that fentanyl may have played a part in the 2018 overdose death in Studio City of rapper Mac Miller; on Nov. 10, a drug dealer from West L.A. pleaded guilty to selling the 26-year-old counterfeit oxycodone pills which contained the substance.

These high-profile tragedies are a window into an opioid epidemic that the National Center for Health Statistics announced in November had claimed more than 100,000 lives in the U.S. during the 12-month period that ended in April — eclipsing car crash and gun fatalities combined. The number has doubled since 2015. Fentanyl has fueled this rise, especially its surreptitious addition to other illegally manufactured drugs.

In Hollywood, where cocaine use has long been a party aid of choice, to the point of caricature, fentanyl’s infiltration into the illicit market has put the entertainment community on edge — what was once simply the risky business of indulgence can now be a far more lethal gamble.

“If you don’t have tolerance, 2 milligrams of fentanyl can kill you,” explains Dr. Nora Volkow, the director of the federal government’s National Institute on Drug Abuse. Adds Timothy Sarquis, co-director of Killer High, a Hulu documentary released in September about the perils of fentanyl, especially for young people: “It’s just a tiny bit, but because their bodies aren’t used to it, it causes them to overdose so quickly.”

The L.A. County Department of Medical Examiner-Coroner tells THR that it had 420 fentanyl-related death cases in 2019, rising to more than 1,000 in 2020. “We’re not done with 2021 yet, but I pretty much see the trend will exceed what we saw in 2020,” says Dr. Ruby Javed, chief of the coroner’s forensic science laboratory division, observing that fentanyl’s mortality rate in the county now outpaces that of heroin and meth.

“It’s laced in everything now,” says L.A. philanthropist and Race to Erase MS founder Nancy Davis, who has started a new nonprofit, Cure Addiction Now, focused on funding advancements in addiction research science. Her son Jason, who had long struggled with sobriety, was found to have had a trace amount of fentanyl in his body when he died in February 2020 of a pulmonary embolism. “People often don’t know that they’re taking it,” continues Davis. “If you get addicted to it, it’s really hard to get off of it. When you hear the word ‘heroin,’ you think that’s as bad as it can get. Magnify that by 50. It seeps so fast into your system.”

Experts say the lacing of fentanyl into other substances is both inadvertent as well as intentional. Contamination of the black-market drug supply can be caused by negligence during manufacture and transport. But there’s also a business incentive among traffickers. Some are simply cutting other drugs with relatively cheap fentanyl. Others want to hook fresh addicts, such as with newfangled speedballs where cocaine acts as an upper and fentanyl replaces heroin as the downer. “People are creating the perfect high,” explains Bill Bodner, chief of the DEA’s Los Angeles field division. “Using one counteracts the negative properties of the other. You can enjoy the fentanyl and be alert [because of the cocaine]; otherwise, you’d fall asleep. Or, with people who enjoy cocaine, they don’t grind their teeth.” Fentanyl increases dopamine levels and can produce euphoria and relaxation.

Local law enforcement first encountered pure fentanyl a half-decade ago, when its street price ran to $200-300 per gram. (Now it’s $100-$150 per gram, while cocaine currently sells for $20-$80 per gram.) “It wasn’t mixed into other drugs and users knew what they had,” says LAPD Hollywood Division narcotics detective James Miller, who began seeing the cocaine mix in more recent years. “Now it’s casual users who aren’t expecting it to be so strong. They’re more likely to succumb.”

Fentanyl’s precursor chemicals are manufactured in China and India. Then the synthetic drug is produced in clandestine Mexican labs. The country’s cartels, whose violence is driven by control of land, have increasingly turned their attention to fentanyl in part because there’s no need to secure territory for crops.

Bodner explains that L.A. is a primary “transshipment hub,” or waystation, for drugs including fentanyl to cross the southwestern U.S. border. At first, fentanyl largely bypassed Los Angeles because local opioid addicts stuck with their preferred narcotic (“This is a big black tar heroin city,” says Bodner), and demand was far greater on the East Coast, where the Oxycontin prescription spigot was being turned off. Beyond cocaine, fentanyl has now infiltrated the counterfeit pressed-pill market, showing up primarily in Oxycodone or Roxycodone (known as Roxies), but also MDMA as well as ersatz Percocet, Xanax and Adderall.

Another factor contributing to the fentanyl crisis is the pandemic’s psychological toll, which has led to new and increased substance abuse and overdoses, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention and the American Medical Association. “The isolation, the shutdowns, the epidemic of loneliness, the desire for escape — it all drives supply, and fentanyl is a cheap way to produce an effect,” explains Ryan Hampton, author of American Fix: Inside the Opioid Addiction Crisis and How to End It.

In a Feb. 7, 2021, Instagram post, Dr. Laura Berman, the relationship therapist and OWN television host, revealed that her 16-year-old son had fatally overdosed in his bedroom while “sheltering at home” after purchasing counterfeit pills from a dealer on Snapchat. (She believed they were Xanax or Percocet and, at the time, was awaiting toxicology results.) “Experimentation gone bad,” she wrote. “He got the drugs delivered to the house.” (Berman didn’t respond to a request for further comment.)

One remedy for the crisis is wider availability of fentanyl test strips, which attempt to detect the presence of the drug in other substances. However, they are not always reliable, especially since final street products are a shifting adversary, chameleonic in their chemical structure. The test strips themselves can also end up abetting the problem, creating a way for fentanyl addicts to find the substance. “I suspect that some of [the rise] is also related to people now getting addicted to fentanyl, and just using more of it,” says Dr. Gary Tsai, division director of substance abuse prevention and control at the L.A. County Department of Public Health. “We’re actually hearing from some of our providers that individuals are using fentanyl test strips not to avoid fentanyl but actually to seek out fentanyl.”

Despite the drawbacks of the strips — which, like clean-needle programs, are part of a controversial approach known as harm-reduction — the situation has become so severe that U.S. Secretary of Health and Human Services Xavier Becerra signaled the Biden administration would work to make them more easily accessible. “We are willing to go places where our opinions and our tendencies have not allowed us to go [before],” he told NPR on Oct. 27, adding: “We are literally trying to give users a lifeline.”

That’s the case at USC, where a new nonprofit, Trojan Awareness Combating Overdose, distributed 1,000 test strips to partygoers in September alone. Over the past five years, several students have died from overdoses caused by taking fentanyl-laced Xanax or cocaine. (According to USC Annenberg Media, during the fall 2019 semester fentanyl claimed three of nine total student deaths.) Based on test strip tracking data from September, “there have been at least a dozen positives [for fentanyl] at the USC campus,” says 2021 graduate Madeline Hilliard, who leads the organization. (Users can scan a QR code to upload anonymous results.)

“The rise of fentanyl has definitely had an effect on nightlife culture,” observes China Morbosa, a musician who’s worked in L.A.’s bar industry for the past decade. “People are nervous to use drugs. Basically, if you don’t have a stash from pre-2020, don’t gamble with it.”

In Other NEWS